August 23, 2019

Python 2 is being deprecated at the end of this year and we’re still teaching it for our robotics competitions? I explain my experiences with various interfaces to control both our robots, and others, and explain why I developed j5.

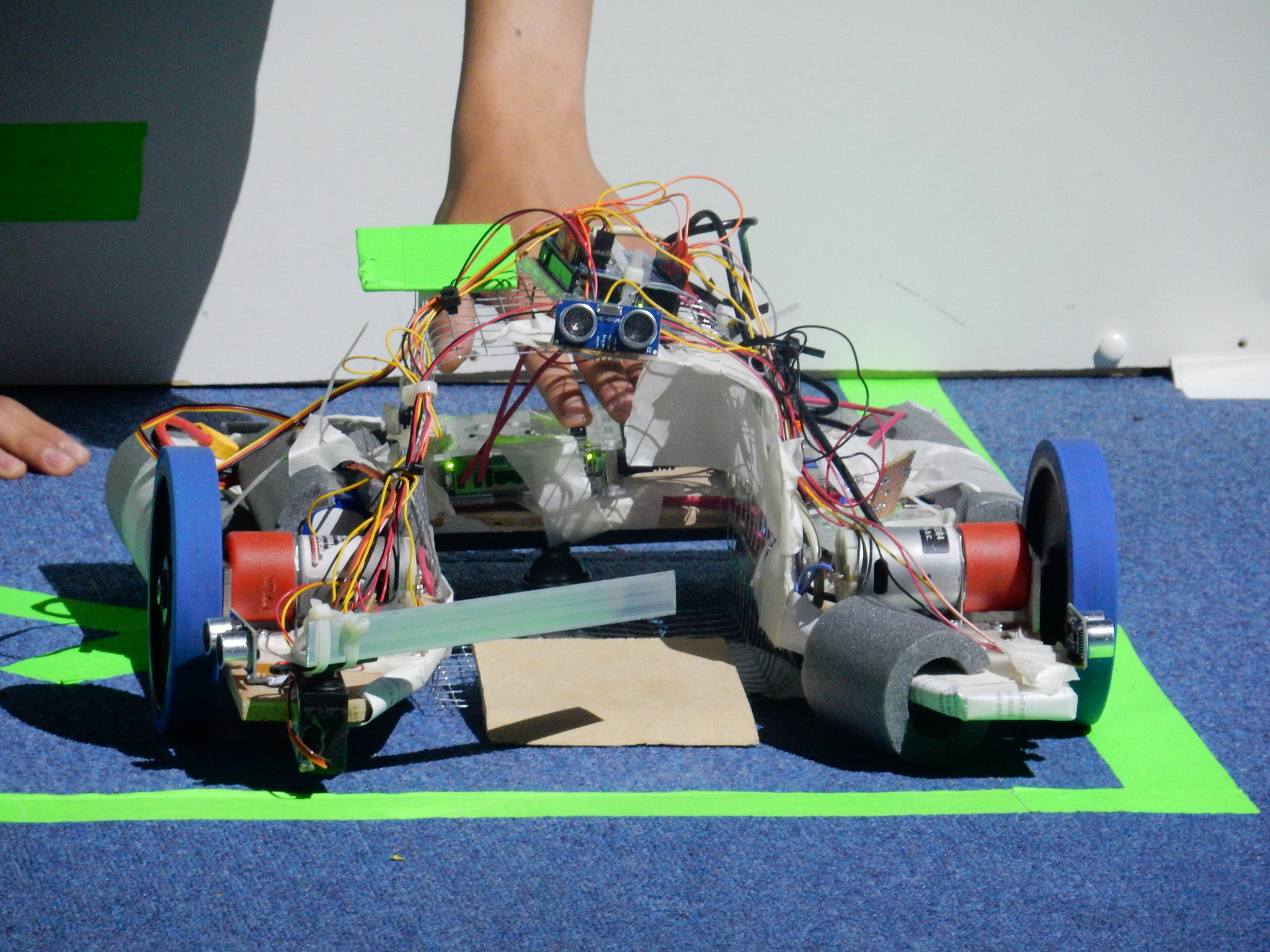

A typical robot built for our competitions

sr.robot

The first API for Student Robotics style robotics kit that I used was sr.robot, which is probably a familiar name to anybody who has ever competed in Student Robotics. Looking further into it, the first reference that I can find is in April 2008, when Rob migrated it from SVN to Git. Looking through the commit history reveals a great deal more about Student Robotics than I have heard from word of mouth alone. The familiar Robot main class didn’t appear until 2011 though, and it looks like a fair amount of history was lost in that move away from SVN.

The modern version of sr.robot has evolved much from the original, but has remained fairly similar since 2011ish. Simple, and effective. The stability of the codebase has remained a very compelling reason to deploy it year after year, despite it being on Python 2. However, the stagnation of the codebase has allowed bugs to appear, which whilst well documented have been left unfixed for a long time.

SourceBots: robot-api and robotd

One of the tools that we ship to competitors for Student Robotics is the “simulator”, essentially a small pygame based model of the arena with a almost identical API to the actual robot softwware. When SourceBots first began development of their kit, the hardware and API were decoupled. Robotd was a daemon that ran in the background and exposed boards that it finds as UNIX-AF sockets in /var/robot. The eventual plan was to have multiple robotd implementations, such as for hardware, simulation and testing. The single robot-api was then able to talk to and control all of them using a common protocol.

A quick diagram of the robotd stack

Another huge step that this iteration of software took was the introduction of Python 3 and partial type hinting. Unit test coverage was present in parts of the project, but mostly covered the protocol between the api and the daemon.

The main issue with this stack was the lack of extensive full stack testing, combined with the use of sockets. Whenever there was an issue with the connection to a board (coming in a blog post soon), robotd would close the socket unexpectedly. In some cases a log would be generated the robotd journal, but this would not be visible to the students. The error that the students would always see, and that became so common that a robot was named after it during SourceBots 2018 was Pipe Error. No more details, not even which board had gone wrong.

From a user experience design perspective, this is disasterous. We spent a long time trying to debug these issues during both deployments of this stack and never managed to get to the bottom of what was going wrong.

However, this experimental design started the chain of development towards the more modern stacks I will talk about below. The authors of it did an absolutely brilliant job, and came up with a great solution given the constraints (mostly time), that they were pressured under.

Robot-API 2

Despite the similar name, robot-api2 is in fact a partial kit stack all by itself. No hardware implementation though, but innovative enough to gain a mention here.

The major leap that Alistair made was bring the control of the robot back into the usercode process, but still having multiple backends, thus allowing us to control different things (hardware, simulator, etc) from the same API. Instead of having loosely defined JSON schemas, going over flakey unix sockets, we now have type-checked interfaces ensuring that the data is what we expected it to be. Alas, it is still sort of dynamically typed, but that’s yet another thing for a future blog post.

I spent some time working on a fork of robot-api2 to implement things further, but I hit problems which this solution did not solve.

For a solution written in an evening, it contains many of the key principles that went on to inspire j5.

RoboCon

I’m going to briefly give a mention to the HR Robocon API which started out as a clone of sr.robot, but with new hardware. It has evolved over time to be quite different to sr.robot and does have Python 3 support there now. It does still have the original copyright statements in it, and is in a legal grey area as sr.robot was never released under an open source licence.

However, I’ve now gone and mentioned three separate organisations that are developing and using very similar software. This results in a large amount of duplicated effort, which we could instead spend on building new features and stability together.

j5: The Future?

j5 is something completely different to all of these that I’ve been talking about. It is not an API by itself, and would be somewhat clunky to use directly as a student. It is however, a framework for building robotics APIs. It takes all of the common features, code, and effort and bundles it into one rigorously tested library.

With j5, a buzzer on a RoboCon board would have exactly the same API as one on an SR board, and the same again as in the simulator. It makes more layers of abstraction than any other previous API, but we end up with something that almost anybody can use at the surface. This means that adding support for your hardware is as simple as creating a Backend and a Board class, everything else just works.

A section of the j5 class diagram

If your hardware is already supported, or maintained by someone else, it is easy to create the most basic API. 20 lines should be more than enough for a MVP of the SR kit. Yet in reality, it will be much more complex. Every competition will implement some of their own details, from the OS through to game specific details like marker sizes.

The first implementation of a j5 based API, sbot was successfully deployed at Smallpeice 2019, with barely a glitch. I plan to write up on exactly what we did encounter, and how we were able to deploy it with so few issues.

j5 has had a few focal points during it’s development, but the one that I’ve been most keen on is User Experience. From useful error messages, through to a short beep when your robot is ready to start, it makes all of the difference when kit is used in a high-stress environment like Smallpeice. Code quality has been at the top of the list too, and I had a great few hours finding the strictest, yet still practical, settings for our linting and testing tools.

So, where next for j5? We have a few things we want to sort out, starting with a properly democratic structure for the project as it’s now got sufficiently large that I can’t go around making decisions by myself. I’m hopeful that Student Robotics will adopt this new API into their next kit stack, and then I guess we’ll have to start talking to competitions that don’t have volunteers already involved in the project.